To learn more about the approach we take to teach a robot to open medicine bottles, please checkout our paper.

1. Introduction

A hallmark of machine intelligence is the capability to adapt to new tasks rapidly and “achieve goals in a wide range of environments”. In comparison, a human can quickly learn new skills by observing other individuals, expanding their repertoire swiftly to adapt to the ever-changing environment. To emulate the similar learning process, the robotics community has been developing the framework of Learning from Demonstration, i.e., LfD. However, the “correspondence problem”, i.e., the difference of embodiments between a human and a robot, is rarely addressed in the prior work of LfD. As a result, a one-to-one mapping is usually handcrafted between the human demonstration and the robot execution, restricting the LfD only to mimic the demonstrator’s low-level motor controls and replicate the (almost) identical procedure to achieve the goal. Such behavior is analogous to a phenomenon called “overimitation” observed in human children.

Obviously, the skills learned from overimitation can hardly be adapted to new robots or new situations.

Inspired by the idea of mirror neurons, we propose a mirroring approach that extends the current LfD, through the physics-based simulation, to address the correspondence problem. Rather than overimitating the motion controls from the demonstration, it is advantageous for the robot to seek functionally equivalent but possibly visually different actions that can produce the same effect and achieve the same goal as those in the demonstration.

To achieve this goal, we take a force-based approach and deploy a low-cost tactile glove to collect human demonstration with fine-grained manipulation forces. Beyond visually observable space, these tactile-enabled demonstrations capture a deeper understanding of the physical world that a robot interacts with, providing an extra dimension to address the correspondence problem. This approach is also goal-oriented in the sense that a “goal” is defined as the desired state of the target object and encoded in a grammar model. We learn a grammar model from demonstrations and allow the robot to reason about the action to achieve the goal state based on the learned grammar.

To show the advantage of our approach, we mirror the human manipulation actions of opening medicine bottles with a child-safety lock to a real Baxter robot. The challenge in this task lies in the fact that opening such bottles requires to push or squeeze various parts, which is visually similar to opening one without a child-safe lock.

2. Pipeline

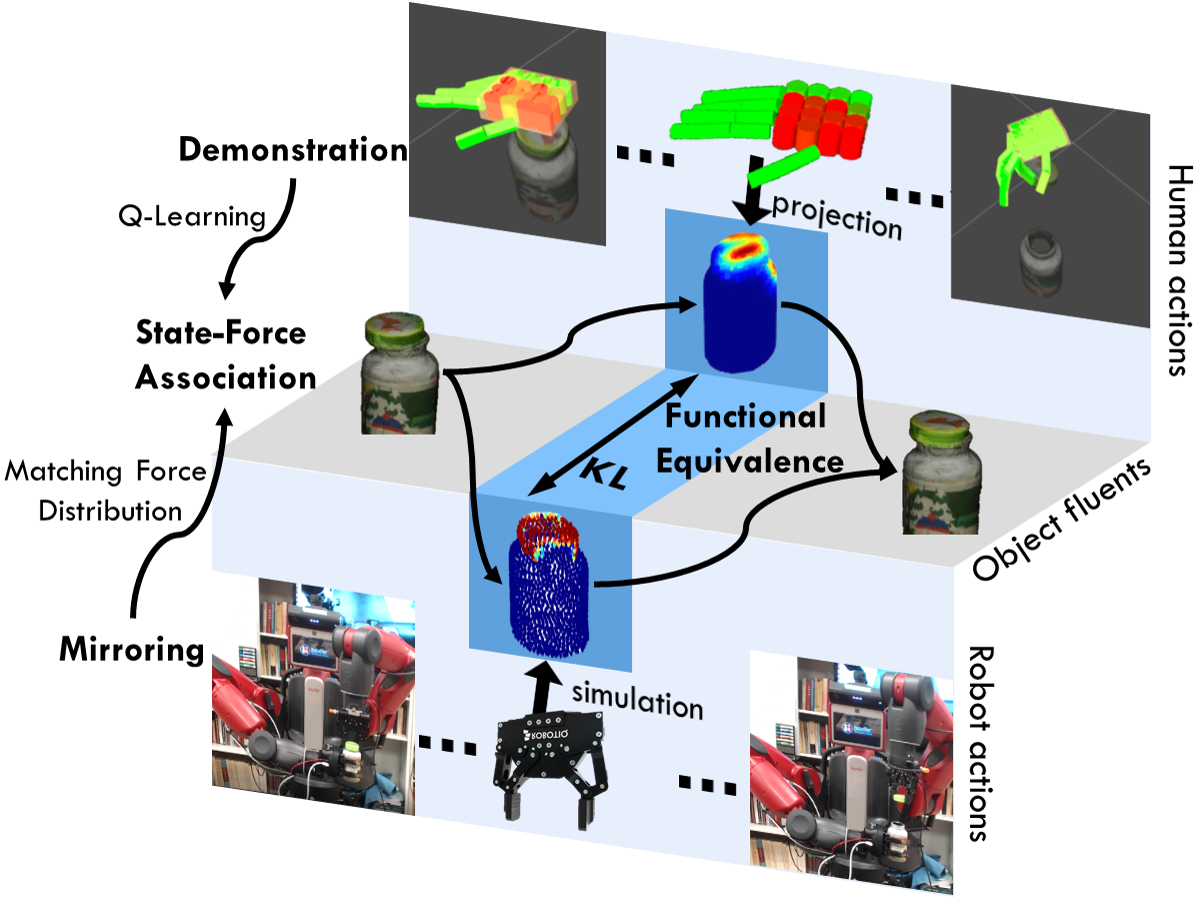

The following figure shows the pipeline of the mirroring approach.

Figure 1. A robot mirrors human demonstrations with functional equivalence by inferring the action that produces similar force, resulting in similar changes of the physical states. Q-Learning is applied to associate types of forces with the categories of the object state changes to produce human-object-interaction (hoi) units.

Figure 1. A robot mirrors human demonstrations with functional equivalence by inferring the action that produces similar force, resulting in similar changes of the physical states. Q-Learning is applied to associate types of forces with the categories of the object state changes to produce human-object-interaction (hoi) units.

After collecting human demonstrations on a specific task (here opening bottles with child-safety lock), we first learn by Q-Learning to associate actions (in the space of forces) and object state changes. The learned policy is further transformed into a grammar representation, i.e., T-AoG. During execution, the robot reasons about the action to take by imagining the result of this action and picks one that would lead to a state change towards the final goal.

3. Force-based Goal-Oriented Mirroring

3.1. Learning Force and State Association

For ease of implementation, we use distributions of forces on objects as the state space of forces and apply K-means clustering to group force distributions generated by different robot actions. Force distributions in a group are then averaged and normalized. For state representation, we discretize the distance and angle of the bottle lid and normalize them into [0, 1]. Finally, we apply the famous Q learning rule in a temporal difference manner to learn the force and state association.

\[Q(s_i, a_i) = (1 - \alpha) Q(s_i, a_i) + \alpha [r(s_i, a_i) + \gamma \max_j Q(s_{i + 1}, a_j)]\]3.2. Learning Goal-Oriented Grammar

The human-object-interaction (hoi) sequence learned by policy naturally forms the space of parse sentences from an implicit grammar. Therefore, we could recover the grammar structure by ADIOS [1] following the posterior probability.

\[p(G | X) \propto p(G) p(X | G) = \frac{1}{Z} e^{-\alpha ||G||} \prod_{pt_i \in X} p(pt_i | G)\]3.3. Mirroring to Robots

To mirror the action to our robots and avoid overimitation, we leverage a physics-based simulator of Neo-Hookean model. The mirrored action is first measured by the force distribution under simulation and then compared to the learned force distribution. The action with minimum distance with the learned force will be chosen. In this paper, we use KL divergence as the distance metric.

4. Experiment

4.1. Setup

We exercise the proposed framework in a robot platform with a dual-armed 7-DoF Baxter robot mounted on a DataSpeed mobility base. The robot is equipped with a ReFlex TakkTile gripper on the right wrist and a Robotiq S85 parallel gripper on the left. The entire system runs on ROS, and the arm motion is planned by MoveIt!.

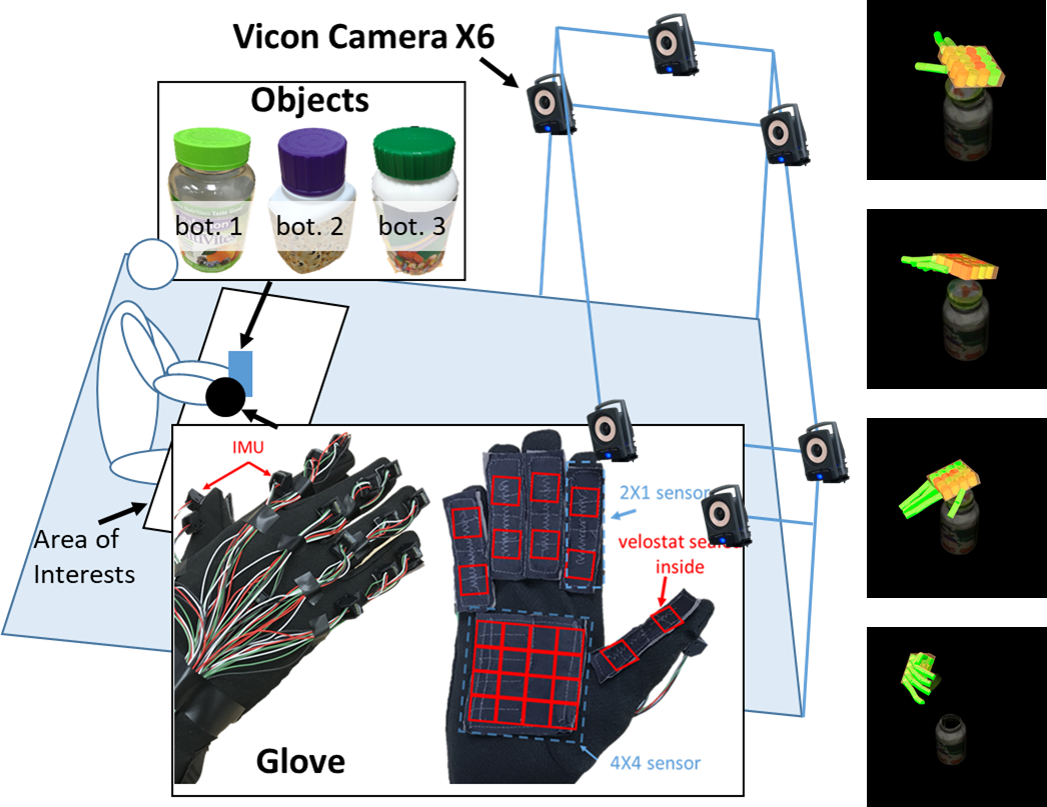

The data collection process is shown in the following figure.

Figure 2. Data collection environment. A tactile glove is utilized to collect hand poses and forces, and the Vicon MoCap system for relative poses of hand and objects.

Figure 2. Data collection environment. A tactile glove is utilized to collect hand poses and forces, and the Vicon MoCap system for relative poses of hand and objects.

The hand pose and force data is collected using an open-sourced tactile glove that is equipped with i) a network of 15 IMUs to measure the rotations between individual phalanxes, and ii) 6 customized force sensors using Velostat, a piezoresistive material, to record the force in two regions (proximal and distal) on each phalange and a 4 \(\times\) 4 regions on palm. The relative poses between the wrist of hand and object parts (i.e., bottle and lid) are obtained from Vicon. The data of 10 human manipulation sequences is collected, processed, and visualized using ROS.

4.2. Robot Execution with Functional Equivalence

After the learning process, we could successfully execute the learned models on a robot. To do that, a parse tree is first sampled from the T-AoG induced from the learned policy to obtain a sequence of force types the robot should imitate in order to cause the same changes of object states. Then the execution of a Baxter robot starts from an initial position and sequentially performs the corresponding primitives. In the following figure, the \(a_6\) downward primitive indeed generates forces which are captured by the force sensor (top left) in the robot wrist, which demonstrate that the mirroring approach indeed allows the robot to fulfill the challenging task of opening medicine bottles with a set of actions that are different from demonstrations.

Figure 3. Starting from the initial pose, the primitives (in grey and denoted by \(a_i\)) are performed sequentially. The robot “pushes” by \(a_6\) (downward) and opens the medicine bottle by \(a_5\) (upward).

Figure 3. Starting from the initial pose, the primitives (in grey and denoted by \(a_i\)) are performed sequentially. The robot “pushes” by \(a_6\) (downward) and opens the medicine bottle by \(a_5\) (upward).

5. Conclusion

We present a force-based, goal-oriented mirroring approach for a robot to learn a manipulation task by learning associations between forces and state changes to avoid overimitation. This approach differs from prior work that either mimics the demonstrator’s trajectory or matches the keypoints, providing a deeper understanding of the physical world for a robot.

In the experiment, we use a tactile glove to collect human demonstrations of opening medicine bottles with safety locks. Successful demonstrations of various bottle openings demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

For numerical results and detailed analysis, please refer to our full paper. If you find the paper helpful, please cite us.

@inproceedings{liu2019mirroring,

author={Liu, Hangxin and Zhang, Chi and Zhu, Yixin and Jiang, Chenfanfu and Zhu, Song-Chun},

title={Mirroring without Overimitation: Learning Functionally Equivalent Manipulation Actions},

booktitle={Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI)},

year={2019}

}

This work is also built on our previous papers [2] and [3].

References

[1] Qi, S., Huang, S., Wei, P., & Zhu, S. C. (2017, August). Predicting human activities using stochastic grammar. In International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), IEEE.

[2] Xie, X., Liu, H., Edmonds, M., Gaol, F., Qi, S., Zhu, Y., … & Zhu, S. C. (2018, May). Unsupervised Learning of Hierarchical Models for Hand-Object Interactions. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 1-9). IEEE.

[3] Edmonds, M., Gao, F., Xie, X., Liu, H., Qi, S., Zhu, Y., … & Zhu, S. C. (2017, September). Feeling the force: Integrating force and pose for fluent discovery through imitation learning to open medicine bottles. In Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on (pp. 3530-3537). IEEE.

-

Previous

Training a Quadcopter to Autonomously Learn to Track -

Next

MetaStyle: Trading Off Speed, Flexibility, and Quality in Neural Style Transfer