This post briefly summarizes our work on causal visual reasoning, i.e., abstract causal reasoning beyond covariation, and in particular, the Abstract Causal REasoning (ACRE) dataset. For further details, please refer to our CVPR 2021 paper.

1. Introduction

“There is something fascinating about science. One gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact.” — Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi.

The history of scientific discovery is full of intriguing anecdotes. Mr. Twain is accurate in summarizing how influential science theories are distilled from sparse and limited investments. From only three observations, Edmond Halley precisely predicted the orbit of the Halley comet and its next visit, which he did not live to see. From a few cathode rays, Joseph Thomson proved and derived the existence of electrons. From merely crossbreeding of pea plants, Gregor Mendel established the laws of Mendelian inheritance much beyond pea plants. Out of many other possible conjectures, pioneering scientists picked the most plausible ones.

The above examples of causal induction are only a few acclaimed cases of omnipresent causal reasoning scenarios in science history and our daily life. In fact, despite the notorious complexity in causal discovery, humans, even young toddlers, can felicitously identify and, sometimes, intervene in the unobservable mechanisms from only a trifling number of samples of observable events.

This captivating commonplace trait of human cognition and its paramount connection to human learning mechanism motivate us to ask a counterpart question for modern Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems:

At what level do current visual reasoning systems induce causal relationships?

To answer this question, we propose the Abstract Causal REasoning (ACRE) dataset. ACRE is inspired by the established stream of research on Blicket detection originally administered to young toddlers. The original experiments designed by Gopnik and Sobel [1] introduced a novel setup for investigating children’s ability of causal induction, in which children were given a special machine referred to as “Blicket detector.” Its underlying mechanism is intuitive: A Blicket detector would activate, lighting up and making noise, when a “Blicket” was put on it. The experimenter demonstrated a series of trials to participants by placing various (combinations of) objects on the Blicket detector and showing whether the detector was activated or not. At length, the participants were asked which object is a Blicket and how to make an (in)activated Blicket machine stop (go).

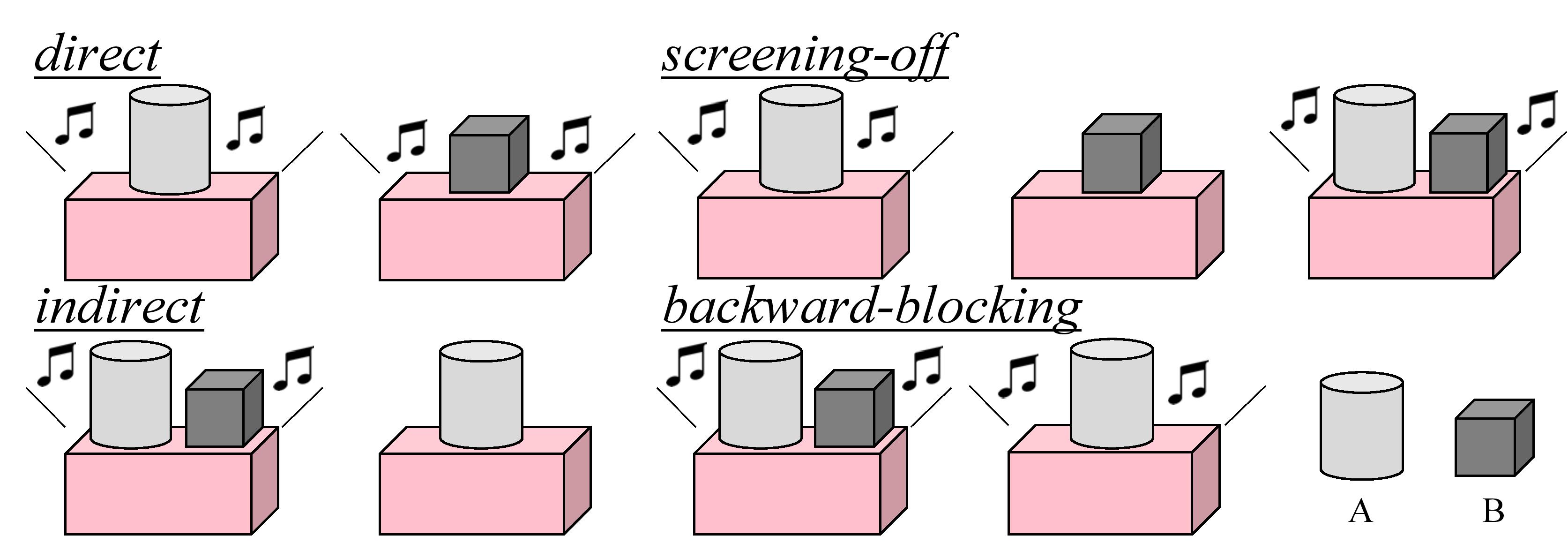

This line of work’s intricate nature lies in how the context and query were designed to test abstract causal reasoning beyond the simple strategy of covariation; see an illustration in Figure 1. As a base test on causal discovery by covariation, Sobel et al. [2] show that children can correctly associate cause and effect using direct evidence. They also show that with only indirect evidence asserting the Blicketness of object B, children still made accurate predictions [3]. However, one must go beyond the simple covariation strategy to discover the hidden causal relations in the screening-off case and the backward-blocking case. Specifically, in the screening-off setting (Figure 1 Top), object B (non-Blicket) is screened-off by A (Blicket) from probabilistically activating the machine [3]. The backward-blocking setting (Figure 1 Bottom) is even more intriguing as object B, not independently tested, has undetermined Blicketness despite the fact that every appearance of it is associated with an activated machine [2].

Figure 1. Abstract causal reasoning tasks administered to human participants. The Blicket machine possesses various activation patterns in these four cases. One needs to discover the hidden causal relations to answer two types of questions: whether object A / B is a Blicket, and how to make the machine stop / go.

Figure 1. Abstract causal reasoning tasks administered to human participants. The Blicket machine possesses various activation patterns in these four cases. One needs to discover the hidden causal relations to answer two types of questions: whether object A / B is a Blicket, and how to make the machine stop / go.

The proposed ACRE dataset is built following a similar querying manner in the Blicket experiments to study how well existing visual reasoning systems can learn to derive ample causal information from scarce observation. In particular, inspired by the recent endeavors of visual reasoning in controlled environments, we adopt the CLEVR universe [4] in ACRE’s design and add a Blicket machine to signal its state of activation, intentionally simplifying visual information processing and emphasizing causal reasoning. Following attempts made in abstract spatial-temporal reasoning benchmarks, we provide the visual reasoning system with sets of panel images as context and use image-based queries to ease language understanding, echoing the setup and the learning theories in developmental literature.

2. Building ACRE

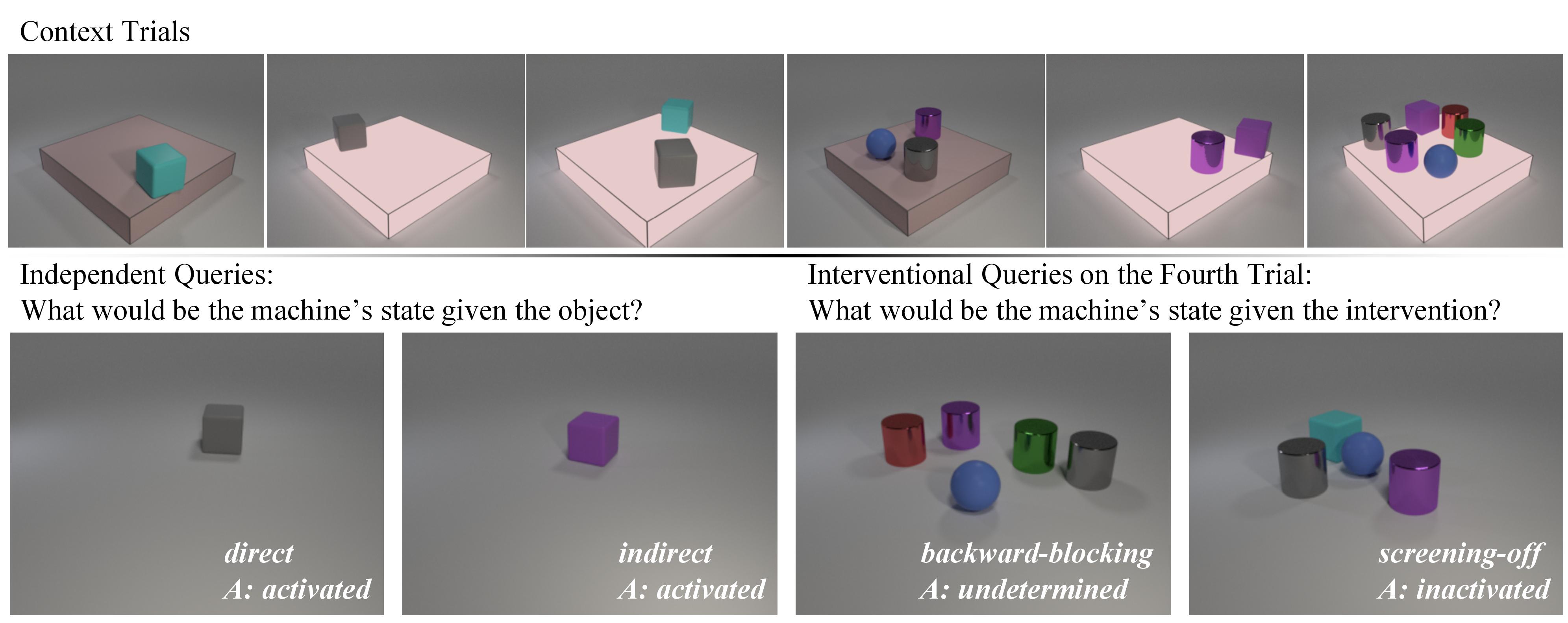

Figure 2. A sample problem in ACRE. Of the \(6\) context trials, we devote the first set of \(3\) panels for an introduction to the Blicket machinery and allow more complex configurations in the second set of panels. Queries are either on independent objects or interventional combinations for an existing trial. In this example, the first query tests causal reasoning from direct evidence, as the gray cube is independently tested and always associated with an activated machine. The second query requires comparing the fourth and fifth trial to realize that the Blicket machine is activated by the cube, not the cylinder, based on indirect evidence. As such, we infer that the red and green cylinders in the sixth trial may not activate the machine because the purple cube can already do so; despite their association with an activated machine only, their Blicketness is backward-blocked in the interventional trial. The cyan cube is screened-off by the gray cube’s Blicketness from probabilistically activating the machine. Of note, the screening-off and the backward-blocking case cannot be solved by covariation.

Figure 2. A sample problem in ACRE. Of the \(6\) context trials, we devote the first set of \(3\) panels for an introduction to the Blicket machinery and allow more complex configurations in the second set of panels. Queries are either on independent objects or interventional combinations for an existing trial. In this example, the first query tests causal reasoning from direct evidence, as the gray cube is independently tested and always associated with an activated machine. The second query requires comparing the fourth and fifth trial to realize that the Blicket machine is activated by the cube, not the cylinder, based on indirect evidence. As such, we infer that the red and green cylinders in the sixth trial may not activate the machine because the purple cube can already do so; despite their association with an activated machine only, their Blicketness is backward-blocked in the interventional trial. The cyan cube is screened-off by the gray cube’s Blicketness from probabilistically activating the machine. Of note, the screening-off and the backward-blocking case cannot be solved by covariation.

The ACRE dataset is designed to be light in visual recognition and heavy in causal induction. Specifically, we ground every panel in a fully-controlled synthetic environment by adopting the CLEVR universe where all objects, including the Blicket machine, are placed on a tabletop with three-point lighting. All potential Blicket objects are of the same size and come with \(3\) possible shapes (cube, sphere, or cylinder), \(2\) possible materials (metal or rubber), and \(8\) possible colors (gray, red, blue, green, brown, cyan, purple, or yellow). For the context panels, we set all objects on a pink Blicket machine at the center of the scene and signal its state of activation by lighting it up. For the query panels, we directly put all objects on the tabletop. In both cases, objects are randomly distributed across the scenes. To avoid confusion during reference, every object is uniquely identifiable by its shape, material, and color. Other than the constraints, every object’s attributes are randomly sampled from the aforementioned space. Collectively, every ACRE problem contains \(5\) to \(8\) unique objects. We keep other scene configurations the same as the original setup in CLEVR and generate images by Blender. Every image is also fully-annotated with object attributes, bounding boxes, and masks; see Figure 2 for a sample problem in ACRE.

Apart from an I.I.D. split, ACRE comes with additional O.O.D. splits to measure model generalization in causal induction; we focus on compositionality and systematicity in systematic generalization. In the compositionality split, we assign different shape-material-color combinations to the training and test set and ensure the training set contains every shape, material, and color, similar to the Compositional Generalization Test (CoGenT) in CLEVR. In the systematicity split, we vary the distribution of an activated Blicket detector in the context panels.

In total, ACRE contains \(30,000\) problems, evenly partitioned into an I.I.D. split, a compositionality split, and a systematicity split. The dataset covers all \(4\) types of queries, and the label distribution is adjusted to be roughly uniform.

3. Reasoning Systems on ACRE

We benchmark two types of reasoning systems: pure deep neural models and the neuro-symbolic combinations.

3.1 Deep Neural Models

As ACRE shares the inductive nature with Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM), we test several established models designed for it, including WReN, LEN, and MXGNet. We also test methods commonly used for linguistic or visual modeling, including CNN, ResNet, LSTM, and BERT. Each context-query pair is independently fed into the network and treated as a classification problem.

3.2 Neuro-Symbolic Models

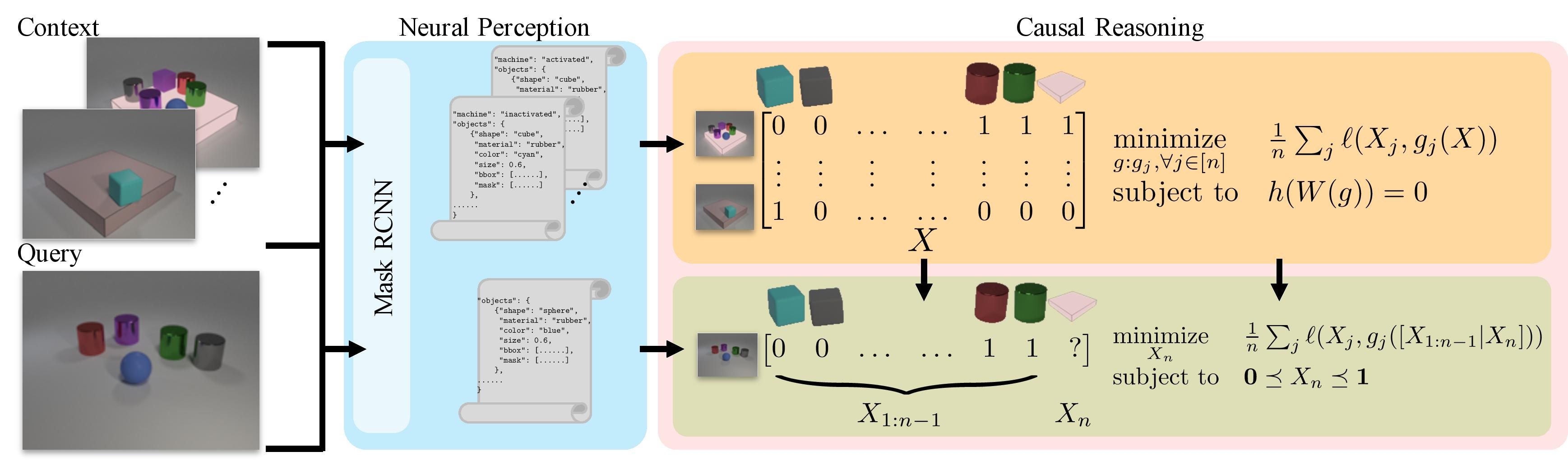

Figure 3. An illustration of the proposed neuro-symbolic combination (NS-Opt) for ACRE. The neural frontend is responsible for scene parsing. In particular, we use a Mask RCNN to detect objects and classify their attributes as well as the Blicket machine’s state. The parsed results are arranged into data matrices and sent into the causal reasoning backend for optimization. A generalized SEM is learned from context trials during reasoning, which is further used to infer the state of the Blicket machine for each query.

Figure 3. An illustration of the proposed neuro-symbolic combination (NS-Opt) for ACRE. The neural frontend is responsible for scene parsing. In particular, we use a Mask RCNN to detect objects and classify their attributes as well as the Blicket machine’s state. The parsed results are arranged into data matrices and sent into the causal reasoning backend for optimization. A generalized SEM is learned from context trials during reasoning, which is further used to infer the state of the Blicket machine for each query.

We draw inspirations from recent advances in neuro-symbolic literature and decompose our model into a neural perception frontend and a causal reasoning backend. By design, the frontend is responsible for parsing each context trial to form an object-based representation, whereas the backend takes the symbolic output from the frontend and performs causal induction; see an overview of the method in Figure 3.

For the neural frontend, we use a Mask RCNN to predict the Blicket machine’s state, object masks, and object attributes (shape, material, and color) for each object in the scene. In the reasoning backend, we use a score-based continuous optimization method, denoted as NS-Opt, to simultaneously learn a generalized Structural Equation Model (SEM) and derive the hidden causal relations [5, 6].

In particular, denoting the existence of object \(j\) in panel \(i\) as \(X_{i, j} \in \{0, 1\}\), we can arrange the symbolic parsing results from the neural perception frontend into a data matrix \(X \in \{0, 1\}^{6 \times n}\), where \(n\) equals the number of unique objects in all context panels plus the Blicket machine. A generalized SEM assumes that the state of object \(j\) is related to states of its parents via a function and can be represented as \begin{equation} X_{j} = f_j(X_{\text{pa}(j)}) = g_j(X), \end{equation} where \(X = [X_1 | X_2 | \ldots | X_j | \ldots]\), and \(\text{pa}(j)\) denotes the parents of object \(j\). The parent finding process is further generalized in \(g_j(\cdot)\) and put into optimization constraints.

The causal discovery problem can then be formulated as \begin{equation} \underset{g: g_j, \forall j \in [n]}{\text{minimize}} \frac{1}{n} \sum_j \ell(X_j, g_j(X)) \text{, subject to } h(W(g)) = 0, \end{equation} where \(W(g)_{k, j} = \left\Vert \partial_k g_j \right\Vert \forall k, j \in [n]\), and \(h(W) = \text{Tr}(e^{W \circ W} - I)\). We use \([n]\) to denote an integer set from \(1\) to \(n\), \(\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert\) the \(L^2\) function norm, and \(\circ\) the Hadamart product. Using the binary cross entropy loss as \(\ell(\cdot, \cdot)\) for each object \(j\), the optimization problem regularizes the generalized SEM to reconstruct the observation, while constraining the relations among the variables to be a causal Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG): \(W(g)\) can be regarded as the adjacency matrix among variables, and \(h(\cdot)\) a metric for acyclicity.

With a learned generalized SEM representing the hidden causal relations in the context trials, we treat each query as another optimization problem. Specifically, we construct a partial data vector for each panel from the symbolic representation parsed by the neural perception frontend. Denoting the Blicket machine as object \(n\), the query vector can be represented as \(X_{1:n - 1}\). Treating \(X_n\) as the probability of the Blicket machine being activated, the query optimization is formulated as \begin{equation} \underset{X_n}{\text{minimize}} \frac{1}{n} \sum_j \ell(X_j, g_j([X_{1:n - 1} | X_n])) \text{, subject to } \mathbf{0} \preceq X_n \preceq \mathbf{1}. \end{equation} We solve it using L-BFGS-B and set thresholds on \(X_n\) to predict the final state of the Blicket machine.

4. Experimental Results

ACRE is equally partitioned into \(3\) splits, i.e., the I.I.D. split, the compositionality (comp) split, and the systematicity (sys) split. Each of the splits contains \(10,000\) problems. We further divide each split into \(10\) folds, with \(6\) folds for training, \(2\) folds for validation, and \(2\) folds for testing. All models are trained on the training sets, with hyper-parameters tuned on the validation sets. Results are reported for the best models on the test sets. In particular, we report two metrics: query accuracy and problem accuracy. The former measures how a model performs on each query, and the later whether a model correctly answers all 4 queries in a problem instance.

The following two tables show how the models perform on different splits of ACRE in general (Table 1) and how they do on each kind of queries (Table 2). Please refer to our paper for a detailed analysis.

| Method | MXGNet | LEN | CNN-MLP | WReN | CNN-LSTM | ResNet-MLP | CNN-BERT | NS-RW | NS-PC | NS-Opt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I.I.D. | Qry. | 33.01% | 38.08% | 40.86% | 40.39% | 41.91% | 42.00% | 43.56% | 46.61% | 59.26% | 66.29% |

| Pro. | 1.00% | 2.05% | 3.25% | 2.30% | 3.60% | 3.35% | 3.50% | 6.45% | 21.15% | 27.00% | |

| Comp. | Qry. | 35.56% | 38.45% | 41.97% | 41.90% | 42.80% | 42.80% | 43.79% | 50.69% | 61.83% | 69.04% |

| Pro. | 1.55% | 2.10% | 2.90% | 2.65% | 2.80% | 2.60% | 2.40% | 8.10% | 22.00% | 31.20% | |

| Sys. | Qry. | 33.43% | 36.11% | 37.45% | 39.60% | 37.19% | 37.71% | 39.93% | 42.18% | 62.63% | 67.44% |

| Pro. | 0.60% | 1.90% | 2.55% | 1.90% | 1.85% | 1.75% | 1.90% | 4.00% | 29.20% | 29.55% |

Table 1. Performances of models on the I.I.D. split, the compositionality split (Comp.), and the systematicity split (Sys.) in ACRE. We report \(2\) evaluation metrics: query accuracy (Qry.) and problem accuracy (Pro.).

| Method | MXGNet | LEN | CNN-MLP | WReN | CNN-LSTM | ResNet-MLP | CNN-BERT | NS-RW | NS-PC | NS-Opt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I.I.D. | D.R. | 27.73% | 49.07% | 55.56% | 51.04% | 48.20% | 54.87% | 52.24% | 88.88% | 84.46% | 91.64% |

| I.D. | 29.63% | 45.11% | 56.31% | 41.04% | 36.76% | 48.37% | 44.50% | 99.29% | 29.33% | 69.25% | |

| S.O. | 14.88% | 33.68% | 44.88% | 29.75% | 53.23% | 42.29% | 42.59% | 7.21% | 78.31% | 85.37% | |

| B.B. | 59.09% | 23.91% | 9.71% | 35.61% | 24.91% | 21.12% | 32.15% | 1.66% | 20.50% | 11.98% | |

| Comp. | D.R. | 36.93% | 47.58% | 57.59% | 55.29% | 56.58% | 62.79% | 54.07% | 91.74% | 89.50% | 92.50% |

| I.D. | 55.99% | 52.51% | 64.38% | 66.94% | 65.10% | 70.01% | 46.88% | 99.80% | 28.66% | 76.05% | |

| S.O. | 0.00% | 18.01% | 31.66% | 8.44% | 19.69% | 30.52% | 40.57% | 4.07% | 85.28% | 88.33% | |

| B.B. | 52.35% | 33.63% | 15.26% | 35.99% | 29.27% | 8.54% | 28.79% | 0.67% | 15.21% | 13.48% | |

| Sys. | D.R. | 15.24% | 46.22% | 70.79% | 53.56% | 42.57% | 65.19% | 55.97% | 92.44% | 89.76% | 94.73% |

| I.D. | 5.42% | 47.90% | 87.61% | 71.35% | 37.61% | 85.07% | 68.25% | 99.89% | 57.08% | 88.38% | |

| S.O. | 42.58% | 30.91% | 11.57% | 16.80% | 63.28% | 9.57% | 0.00% | 0.20% | 73.93% | 82.76% | |

| B.B. | 56.38% | 24.89% | 3.60% | 31.62% | 8.70% | 13.38% | 45.59% | 0.46% | 24.88% | 16.06% |

Table 2. A closer look at how models perform on each type of queries on different splits of ACRE: direct (D.R.), indirect (I.D.), screening-off (S.O.), and backward-blocking (B.B.).

5. Conclusion

In this work, we present a new dataset for Abstract Causal REasoing (ACRE), aiming to measure and improve causal induction in visual reasoning systems. Apart from the inductive reasoning nature, the defining feature of the ACRE dataset is the requirement to perform causal reasoning beyond covariation. Inspired by the established stream of research on Blicket experiments, the ACRE dataset is grounded on a similar setting using the synthetic CLEVR universe. To measure causal induction beyond covariation, we challenge a visual reasoning system with \(4\) types of queries in either independent scenarios or interventional scenarios: direct, indirect, screening-off, and backward-blocking. To better measure generalization in causal discovery, we further propose the compositionality and the systematicity O.O.D. split.

We devise an optimization-based neuro-symbolic method to equip a visual reasoning system with the causal discovery ability. In particular, we decompose the model into a neural perception frontend and a causal reasoning backend. The neural perception frontend parses a given trial using a Mask RCNN, whereas the causal reasoning backend performs continuous optimization for causal discovery. The context trials are leveraged to learn a generalized SEM, and the answer to a query trial is solved by finding the best value to fit the SEM. As the first attempt, we separately train the two components, leaving the problem of closing the loop between visual perception and causal discovery for future work.

Existing visual reasoning systems’ causal induction capability has been benchmarked on ACRE. Specifically, we notice that pure neural models tend to perform causal reasoning by capturing the statistical correlation, achieving satisfactory results on direct and indirect queries but failing on screening-off and backward-blocking ones. For neuro-symbolic models, we notice that all of them struggle on backward-blocking and that the sparse and limited observation further adds to the complexity of the problem. Comparing performances of these \(2\) types of models on various queries, we hypothesize that further combining learning and symbolic reasoning would be a promising direction for causal induction and broader causal reasoning problems.

At length, we hope challenges in this causal reasoning task would call for attention into visual systems with human-level spatial, temporal, and causal reasoning ability.

If you find the paper helpful, please cite us.

@inproceedings{zhang2021abstract,

title={Abstract Spatial-Temporal Reasoning via Probabilistic Abduction and Execution},

author={Zhang, Chi and Jia, Baoxiong and Zhu, Song-Chun and Zhu, Yixin},

booktitle={Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)},

year={2021}

}

References

[1] Gopnik, Alison, and David M. Sobel. “Detecting blickets: How young children use information about novel causal powers in categorization and induction.” Child development 71.5 (2000): 1205-1222.

[2] Sobel, David M., Joshua B. Tenenbaum, and Alison Gopnik. “Children’s causal inferences from indirect evidence: Backwards blocking and Bayesian reasoning in preschoolers.” Cognitive science 28.3 (2004): 303-333.

[3] Gopnik, Alison, et al. “Causal learning mechanisms in very young children: two-, three-, and four-year-olds infer causal relations from patterns of variation and covariation.” Developmental psychology 37.5 (2001): 620.

[4] Johnson, Justin, et al. “Clevr: A diagnostic dataset for compositional language and elementary visual reasoning.” Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2017.

[5] Zheng, Xun, et al. “DAGs with NO TEARS: Continuous Optimization for Structure Learning.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31 (2018): 9472-9483.

[6] Zheng, Xun, et al. “Learning sparse nonparametric DAGs.” International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. PMLR, 2020.

-

Previous

Abstract Spatial-Temporal Reasoning via Probabilistic Abduction and Execution -

Next

Learning Algebraic Representation for Systematic Generalization in Abstract Reasoning