This post briefly summarizes our work on the ALgebra-Aware Neuro-Semi-Symbolic (ALANS) learner for Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM). For further details, please refer to our ECCV 2022 paper. It is a follow-up work of PrAE in the CVPR 2021 paper: ALANS relaxes the requirement of knowledge in PrAE, and adopts on-the-fly optimization to perform induction instead of abduction.

Fun fact: The work is very likely my last conference paper during PhD at UCLA. And the counter for my first-authored publication before graduation should stop at 6, neither too many nor too few. I feel lucky to work on an interesting problem, though, to be honest, the problem itself does not raise too much interest from the community. But that’s fine for me; I don’t need to compete with increasingly higher numbers on popular benchmarks and neither do I need to worry too much about compute. Over the years, this work discussed here is my favorite: I know there are many limitations, the problem scope is not large enough, and the method reuiqres quite a lot of ad-hoc designs to work, but I personally find it fun during the process to come up with this idea, a method that explicitly induces relations and adjusts its own problem representation during learning; this is in sharp contrast against just training different neural networks. I was fortunate to have works nearly immediately accepted after the first submission in my early PhD and only experienced rejections later, especially this work. The work was finished about NeurIPS 2020, then it went through ICLR 2021, CVPR 2021, ICML 2021, NeurIPS 2021, ICLR 2022, CVPR 2022, before finally getting accepted in ECCV 2022. There were reviewers that were reasonable and others that were simply mean and did not understand the work. As a reviewer myself, I know there are conflicts of interest. But I will stop here. In general, I learn to be calm about rejections but can’t help feeling happy about acceptance. I will treat it as a good ending for my PhD, and hopefully it is just the end of the beginning.

1. Introduction

“Thought is in fact a kind of Algebra.” — William James, The Principles of Psychology.

Imagine you are given two alphabetical sequences of \(c, b, a\) and \(d, c, b\), and asked to fill in the missing element in \(e, d, ?\). In nearly no time will one realize the answer to be \(c\). However, more surprising for human learning is that, effortlessly and instantaneously, we can “freely generalize” the solution to any partial consecutive ordered sequences. While believed to be innate in early development for human infants, such systematic generalizability has constantly been missing and proven to be particularly challenging in existing connectionist models. In fact, such an ability to entertain a given thought and semantically related contents strongly implies an abstract algebra-like treatment; in literature, it is referred to as the “language of thought” [1], “physical symbol system” [2], and “algebraic mind” [3]. However, in stark contrast, existing connectionist models tend only to capture statistical correlation, rather than providing any account for a structural inductive bias where systematic algebra can be carried out to facilitate generalization.

This contrast instinctively raises a question—what constitutes such an algebraic inductive bias? We argue that the foundation of modeling counterpart to the algebraic treatment in early human development lies in algebraic computations set up on mathematical axioms, a form of formalized human intuition and the beginning of modern mathematical reasoning. Of particular importance to the algebra’s basic building blocks is the Peano Axiom [4]. In the Peano Axiom, the essential components of algebra, the algebraic set, and corresponding operators over it, are governed by three statements: (1) the existence of at least one element in the field to study (“zero” element), (2) a successor function that is recursively applied to all elements and can, therefore, span the entire field, and (3) the principle of mathematical induction. Building on such a fundamental axiom, we begin to form the notion of an algebraic set and induce the operator to construct an algebraic structure. We hypothesize that such an algebraic treatment set up on fundamental axioms is essential for a model’s systematic generalizability, the lack of which will only make it sub-optimal.

To demonstrate the benefits of adopting such an algebraic treatment in systematic generalization, we showcase a prototype for Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM), an exemplar task for abstract spatial-temporal reasoning. In this task, an agent is given an incomplete \(3\times3\) matrix consisting of eight context panels with the last one missing, and asked to pick one answer from a set of eight choices that best completes the matrix. Human’s reasoning capability of solving this abstract reasoning task has been commonly regarded as an indicator of “general intelligence” and “fluid intelligence”. In spite of the task being one that ideally requires abstraction, algebraization, induction, and generalization, recent endeavors unanimously propose pure connectionist models that attempt to circumvent such intrinsic cognitive requirements. However, these methods’ inefficiency is also evident in systematic generalization; they struggle to extrapolate to domains beyond training, shown also in this paper.

To address the issue, we introduce an ALgebra-Aware Neuro-Semi-Symbolic (ALANS) learner. At a high-level, the ALANS learner is embedded in a general neuro-symbolic architecture but has the on-the-fly operator learnability, hence semi-symbolic. Specifically, it consists of a neural visual perception frontend and an algebraic abstract reasoning backend. For each RPM instance, the neural visual perception frontend first slides a window over each panel to obtain the object-based representation for every object. A belief inference engine latter aggregates all object-based representation in each panel to produce the probabilistic belief state. The algebraic abstract reasoning backend then takes the belief states of the eight context panels, treats them as snapshots on an algebraic structure, lifts them into a matrix-based algebraic representation built on the Peano Axiom and the representation theory [5], and induces the hidden operator in the algebraic structure by solving an inner optimization. The answer’s algebraic representation is predicted by executing the induced operator: its corresponding set element is decoded by isomorphism, and the final answer is selected as the one most similar to the prediction.

2. The ALANS Learner

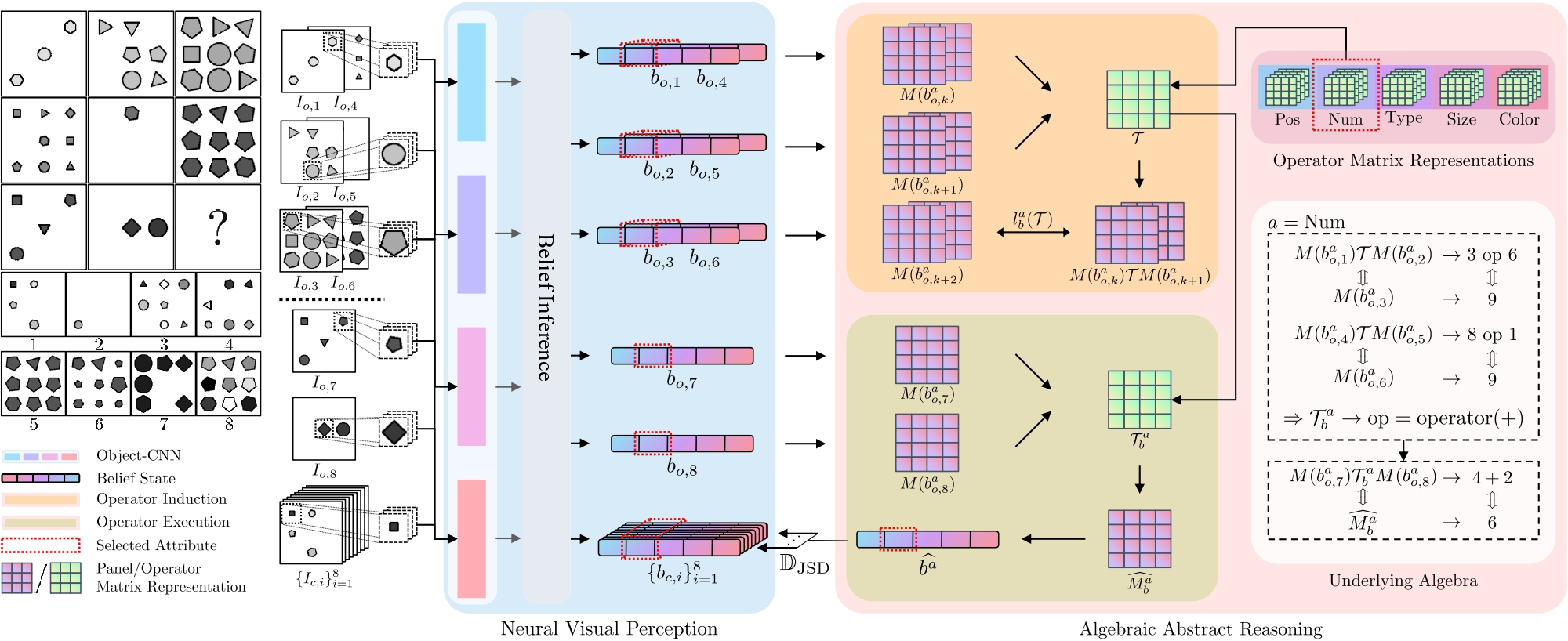

Figure 1. An overview of the ALANS learner. For an RPM instance, the neural visual perception module produces the belief states for all panels: an object CNN extracts object attribute distributions for each image region, and a belief inference engine marginalizes them out to obtain panel attribute distributions. For each panel attribute, the algebraic abstract reasoning module transforms the belief states into matrix-based algebraic representation and induces hidden operators by solving inner optimizations. The answer representation is obtained by executing the induced operators, and the choice most similar to the prediction is selected as the solution. An example of the underlying discrete algebra and its correspondence is also shown on the right.

Figure 1. An overview of the ALANS learner. For an RPM instance, the neural visual perception module produces the belief states for all panels: an object CNN extracts object attribute distributions for each image region, and a belief inference engine marginalizes them out to obtain panel attribute distributions. For each panel attribute, the algebraic abstract reasoning module transforms the belief states into matrix-based algebraic representation and induces hidden operators by solving inner optimizations. The answer representation is obtained by executing the induced operators, and the choice most similar to the prediction is selected as the solution. An example of the underlying discrete algebra and its correspondence is also shown on the right.

In each RPM instance, an agent is given an incomplete \(3\times3\) panel matrix with the last entry missing and asked to induce the operator hidden in the matrix and choose from eight choice panels one that follows it. Formally, let the answer variable be denoted as \(y\), the context panels as \(\{I_{o, i}\}_{i=1}^8\), and choice panels as \(\{I_{c, i}\}_{i=1}^8\). Then the problem can be formulated as estimating \(P(y \mid \{I_{o, i}\}_{i=1}^8, \{I_{c, i}\}_{i=1}^8)\). According to the common design, there is one operator that governs each panel attribute. Hence, by assuming independence among attributes, we propose to factorize the probability of \(P(y = n \mid \{I_{o, i}\}_{i=1}^8, \{I_{c, i}\}_{i=1}^8)\) as

\[\prod_a \sum_{\mathcal{T}^a} P(y^a = n \mid \mathcal{T}^a, \{I_{o, i}\}_{i=1}^8, \{I_{c, i}\}_{i=1}^8) \times P(\mathcal{T}^a \mid \{I_{o, i}\}_{i=1}^8),\]where \(y^a\) denotes the answer selection based only on attribute \(a\) and \(\mathcal{T}^a\) the operator on \(a\).

2.1. Overview

As shown in Figure 1, the ALANS learner decomposes the process into perception and reasoning: the neural visual perception frontend extracts the belief states from each of the sixteen panels, whereas the algebraic abstract reasoning backend views an instance as an example in an abstract algebra structure, transforms belief states into algebraic representation by the representation theory, induces the hidden operators, and executes the operators to predict the representation of the answer. Therefore, in the equation above, the operator distribution is modeled by the fitness of an operator and the answer distribution by the distance between the predicted representation and that of a candidate.

The design for neural visual perception largely follows our previous work of PrAE so I will skip this part and focus instead on the algebraic abstract reasoning backend.

2.2. Algebraic Abstract Reasoning

Given the belief states of both context and choice panels from the visual perception frontend, the algebraic abstract reasoning backend concerns the induction of hidden operators and the prediction of answer representation for each attribute. The fitness of induced operators is used for estimating the operator distribution and the difference between the prediction and the choice panel for estimating the answer distribution.

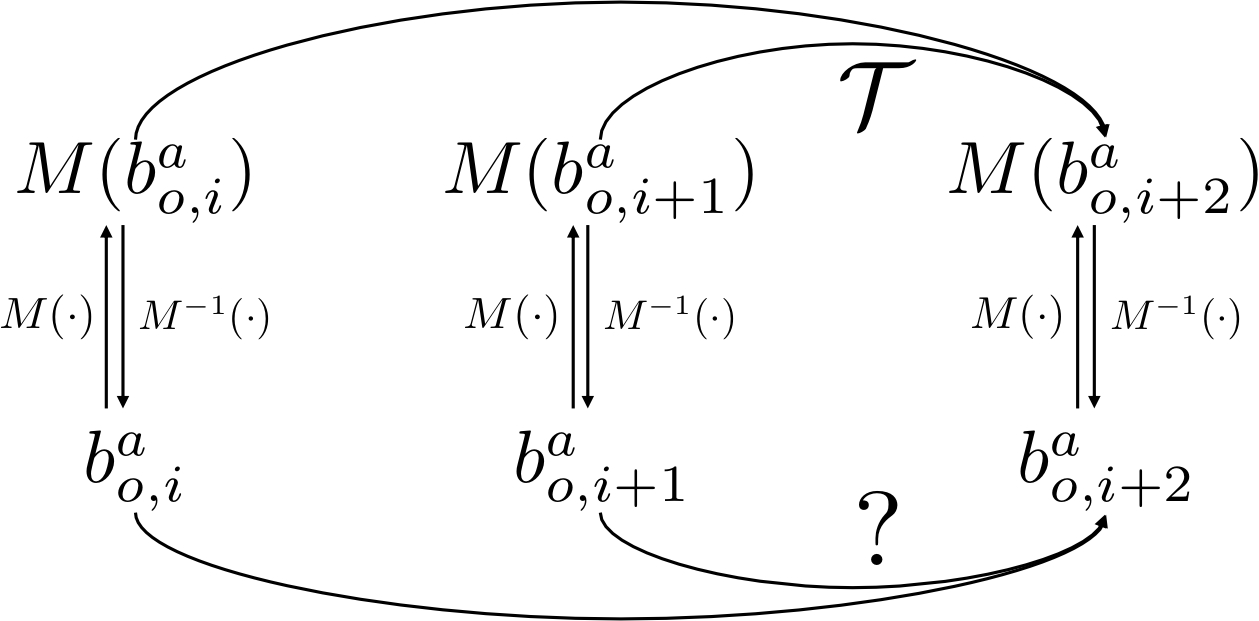

Algebraic Representation. A systematic algebraic view allows us to felicitously recruit ideas in the representation theory [5] to glean the hidden properties in the abstract structures: it makes abstract algebra amenable by reducing it onto linear algebra. Following the same spirit, we propose to lift both the set elements and the hidden operators to a learnable matrix space. To encode the set element, we employ the Peano Axiom [4]. According to the Peano Axiom, an integer-indexed set can be constructed by (1) a zero element (\(\mathbf{0}\)), (2) a successor function (\(S(\cdot)\)), and (3) the principle of mathematical induction, such that the \(k\)th element is encoded as \(S^k(\mathbf{0})\). Specifically, we instantiate the zero element as a learnable matrix \(M_0\) and the successor function as the matrix-matrix product parameterized by \(M\). In an attribute-specific manner, the representation of an attribute taking the \(k\)th value is \((M^a)^k M^a_0\). For operators, we consider them to live in a learnable matrix group of a corresponding dimension, such that the action of an operator on a set can be represented as matrix multiplication. Such algebraic representation establishes an isomorphism between the matrix space and the abstract algebraic structure: abstract elements on the algebraic structure have a bijective mapping to/from the matrix space, and inducing the abstract relation can be reduced to solving for a matrix operator. See Figure 2 for a graphical illustration of the isomorphism.

Figure 2. Isomorphism between the abstract algebra and the matrix-based representation. Operator induction is now reduced to solving for a matrix

Figure 2. Isomorphism between the abstract algebra and the matrix-based representation. Operator induction is now reduced to solving for a matrix

Operator Induction. Operator induction concerns about finding a concrete operator in the abstract algebraic structure. By the property of closure, we formulate it as an inner-level regularized linear regression problem: a binary operator \(\mathcal{T}^a_b\) in a group example for attribute \(a\) minimizes \(\text{argmin}_\mathcal{T} \ell^a_b(\mathcal{T})\) defined as

\[\ell^a_b(\mathcal{T}) = \sum_i \mathbb{E} \left[\Vert M(b^a_{o, i}) \mathcal{T} M(b^a_{o, i + 1}) - M(b^a_{o, i + 2}) \Vert^2_F \right] + \lambda^a_b \Vert \mathcal{T} \Vert^2_F, \label{eqn:binary}\]where under visual uncertainty, we take the expectation with respect to the distributions in the belief states of context panels \(P(b^a_{o, i})\) in the first two rows, and denote its algebraic representation as \(M(b^a_{o, i})\). For unary operators, one operand can be treated as constant and absorbed into \(\mathcal{T}\). Note that the problem admits a closed-form solution. Therefore, the operator can be learned and adapted for different instances of binary relations and concluded on the fly. Such a design also simplifies the recent neuro-symbolic approaches, where every single symbol operator needs to be hand-defined. Instead, we only specify an inner-level optimization framework and allow symbolic operators to be quickly induced based on the neural observations, while keeping the semantic interpretability in the neuro-symbolic methods. Therefore, we term such a design semi-symbolic.

The operator probability is then modeled by each operator type’s fitness, e.g., for binary,

\[P(\mathcal{T}^a = \mathcal{T}^a_b \mid \{I_{o, i}\}^8_{i = 1})\, \propto\, \exp(-\ell^a_b(\mathcal{T}^a_b)).\]Operator Execution. To predict the algebraic representation of the answer, we solve another inner-level optimization similar to the induction process, but now treating the representation of the answer as a variable:

\[\widehat{M^a_b} = \text{argmin}_M \ell^a_b(M) = \mathbb{E}[\Vert M(b^a_{o, 7}) \mathcal{T}^a_b M(b^a_{o, 8}) - M \Vert^2_F],\]where the expectation is taken with respect to context panels in the last row. The optimization also admits a closed-form solution, which corresponds to the execution of the induced operator.

The predicted representation is decoded probabilistically as the predicted belief state of the solution,

\[P(\widehat{b^a} = k \mid \mathcal{T}^a)\, \propto\, \exp(-\Vert \widehat{M^a} - (M^a)^k M^a_0 \Vert^2_F).\]Answer Selection. Estimating the answer distribution is now boiled down to estimating the conditional answer distributions for each attribute. Here, we propose to model it based on the Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD) of the predicted belief state and that of a choice,

\[P(y^a = n \mid \mathcal{T}^a, \{I_{o, i}\}_{i=1}^8, \{I_{c, i}\}_{i=1}^8)\, \propto\, \exp(-d_n^a),\]where we define \(d_n^a\) as

\[d_n^a = \mathbb{D}_\text{JSD}(P(\widehat{b^a} \mid \mathcal{T}^a) \Vert P(b^a_{c, n}))).\]3. Experiments

A cognitive architecture with systematic generalization is believed to demonstrate the following three principles: (1) systematicity, (2) productivity, and (3) localism. Systematicity requires an architecture to be able to entertain “semantically related” contents after understanding a given thought. Productivity states the awareness of a constituent implies that of a recursive application of the constituent; vice versa for localism.

To verify the effectiveness of an algebraic treatment in systematic generalization, we showcase the superiority of the proposed ALANS learner on the three principles in the abstract spatial-temporal reasoning task of RPM. Specifically, we use the generation methods proposed in RAVEN and I-RAVEN to generate RPM problems and carefully split training and testing to construct the three regimes:

- Systematicity: the training set contains only a subset of instances for each type of relation, while the test set all other relation instances.

- Productivity: as the binary relation results from a recursive application of the unary relation, the training set contains only unary relations, whereas the test set only binary relations.

- Localism: the training and testing sets in the productivity split are swapped to study localism.

| Method | MXGNet | ResNet+DRT | ResNet | HriNet | LEN | WReN | SCL | CoPINet | ALANS | ALANS-Ind | ALANS-V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematicity | 20.95% | 33.00% | 27.35% | 28.05% | 40.15% | 35.20% | 37.35% | 59.30% | 78.45% | 52.70% | 93.85% |

| Productivity | 30.40% | 27.95% | 27.05% | 31.45% | 42.30% | 56.95% | 51.10% | 60.00% | 79.95% | 36.45% | 90.20% |

| Localism | 28.80% | 24.90% | 23.05% | 29.70% | 39.65% | 38.70% | 47.75% | 60.10% | 80.50% | 59.80% | 95.30% |

| Average | 26.72% | 28.62% | 25.82% | 29.73% | 40.70% | 43.62% | 45.40% | 59.80% | 79.63% | 48.65% | 93.12% |

| Systematicity | 13.35% | 13.50% | 14.20% | 21.00% | 17.40% | 15.00% | 24.90% | 18.35% | 64.80% | 52.80% | 84.85% |

| Productivity | 14.10% | 16.10% | 20.70% | 20.35% | 19.70% | 17.95% | 22.20% | 29.10% | 65.55% | 32.10% | 86.55% |

| Localism | 15.80% | 13.85% | 17.45% | 24.60% | 20.15% | 19.70% | 29.95% | 31.85% | 65.90% | 50.70% | 90.95% |

| Average | 14.42% | 14.48% | 17.45% | 21.98% | 19.08% | 17.55% | 25.68% | 26.43% | 65.42% | 45.20% | 87.45% |

Table 1. Model performance on different aspects of systematic generalization. The performance is measured by accuracy on the test sets. Upper half: results on datasets generated by the RAVEN method. Lower half: results on datasets generated by the I-RAVEN method.

Table 1 shows the performance of various models on systematic generalization, i.e., systematicity, productivity, and localism. Compared to results reported in existing works mentioned above, all pure connectionist models experience a devastating performance drop when it comes to the critical cognitive requirements on systematic generalization, indicating that pure connectionist models fail to perform abstraction, algebraization, induction, or generalization needed in solving the abstract reasoning task; instead, they seem to only take a shortcut to bypass them.

Embedded in a neural-semi-symbolic framework, the proposed ALANS learner improves on systematic generalization by a large margin. With an algebra-aware design, the model is considerably stable across different principles of systematic generalization. The algebraic representation learned in relations of either a constituent or a recursive composition naturally supports productivity and localism, while semi-symbolic inner optimization further allows various instances of an operator type to be induced from the algebraic representation and boosts systematicity. The importance of the algebraic representation is made more significant in the ablation study: ALANS-Ind, with algebraic representation replaced by independent encodings and the algebraic isomorphism broken, shows inferior performance. We also examine the performance of the learner with perfect visual annotations (denoted as ALANS-V) to see how the proposed algebraic reasoning module works: the gap despite of accurate perception indicates space for improvement for the inductive reasoning part of the model.

Apart from being superior in systematic generalization, ALANS is also performant on the in-distribution setup. Besides, the model learns to “see” and “reason” during the training process. Please refer to our paper for detailed explanation.

5. Conclusion

In this work, we propose the ALgebra-Aware Neuro-Semi-Symbolic (ALANS) learner, echoing a normative theory in the connectionist-classicist debate that an algebraic treatment in a cognitive architecture should improve a model’s systematic generalization ability. In particular, the ALANS learner employs a neural-semi-symbolic architecture, where the neural visual perception module is responsible for summarizing visual information and the algebraic abstract reasoning module transforms it into algebraic representation with isomorphism established by the Peano Axiom and the representation theory, conducts operator induction, and executes it to arrive at an answer. In three RPM domains reflective of systematic generalization, the proposed ALANS learner shows superior performance compared to other pure connectionist baselines.

The proposed ALANS learner also bears some limitations. For one thing, we make the assumption in our formulation that relations on different attributes are independent and can be factorized. For another, we assume a fixed and known space for each attribute in the perception module, while in the real world the space for one attribute could be dynamically changing. In addition, the reasoning module is sensitive to perception uncertainty as has already been discussed in the experimental results. Besides, the gap between perfection and the status quo in reasoning remains to be filled. In this work, we only show how the hidden operator can be induced with regularized linear regression via the representation theory. However, more elaborate differentiable optimization problems can certainly be incorporated for other problems.

With the limitation in mind, we hope that this preliminary study could inspire more research on incorporating algebraic structures into current connectionist models and help address challenging modeling problems.

If you find the paper helpful, please cite us.

@inproceedings{zhang2022learning,

title={Learning Algebraic Representation for Systematic Generalization in Abstract Reasoning},

author={Zhang, Chi and Xie, Sirui and Jia, Baoxiong and Wu, Ying Nian and Zhu, Song-Chun and Zhu, Yixin},

booktitle={Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV)},

year={2022}

}

References

[1] Fodor, Jerry A. The language of thought. Vol. 5. Harvard university press, 1975.

[2] Newell, Allen. “Physical symbol systems.” Cognitive science 4.2 (1980): 135-183.

[3] Marcus, Gary F. The algebraic mind: Integrating connectionism and cognitive science. MIT press, 2003.

[4] Peano, Giuseppe. Arithmetices principia: Nova methodo exposita. Fratres Bocca, 1889.

[5] Humphreys, James E. Introduction to Lie algebras and representation theory. Vol. 9. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.