This post briefly summarizes our work on the Probabilistic Abduction and Execution (PrAE) learner for Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM). For further details, please refer to our CVPR 2021 paper.

1. Introduction

While “thinking in pictures”, or spatial-temporal reasoning, is effortless and instantaneous for humans, this significant ability has proven to be particularly challenging for current machine vision systems. Recent computational studies on the problem focus on an abstract reasoning task relying heavily on this ablity of “thinking in pictures”—Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM). In this task, a subject is asked to pick a correct answer that best fits an incomplete figure matrix to satisfy the hidden governing rules. The ability to solve RPM-like problems is believed to be critical for generating and conceptualizing solutions to multi-step problems. It is also believed to be characteristic of relational and analogical reasoning and an indicator of one’s fluid intelligence.

State-of-the-art algorithms incorporating a contrasting mechanism and perceptual inference have achieved decent performance in terms of accuracy. Nevertheless, along with the improved accuracy from deep models come critiques on its transparency, interpretability, generalization, and difficulty to incorporate knowledge. Without explicitly distinguishing perception and reasoning, existing methods use a monolithic model to learn correlation, sacrificing transparency and interpretability in exchange for improved performance. Furthermore, as shown in experiments, deep models nearly always overfit to the training regime and cannot properly generalize. Such a finding is consistent with Fodor [1] and Marcus’s [2, 3] hypothesis that human-level systematic generalizability is hardly compatible with classic neural networks; Marcus postulates that a neuro-symbolic architecture should be recruited for human-level generalization.

Another defect of prior methods is the lack of top-down and bottom-up reasoning: Human reasoning applies a generative process to abduce rules and execute them to synthesize a possible solution in mind, and discriminatively selects the most similar answer from choices. This bi-directional reasoning is in stark contrast to discriminative-only models, solely capable of making a categorical choice.

Psychologists also call for weak attribute supervision in RPM. As isolated Amazonians, absent of schooling on primitive attributes, could still correctly solve RPM [4, 5], an ideal computational counterpart should be able to learn it absent of visual attribute annotations. This weakly-supervised setting introduces unique challenges: How to jointly learn these visual attributes given only ground-truth images? With uncertainties in perception, how to abduce hidden logic relations from it? How about executing the symbolic logic on inaccurate perception to derive answers?

To support cross-configuration generalization and answer generation, we move a step further towards a neuro-symbolic model with explicit logical reasoning and human-like generative problem-solving while addressing the challenges. Specifically, we propose the Probabilistic Abduction and Execution (PrAE) learner; central to it is the process of abduction and execution on the probabilistic scene representation. Inspired by Fodor, Marcus, and neuro-symbolic reasoning, the PrAE learner disentangles the previous monolithic process into two separate modules: a neural visual perception frontend and a symbolic logical reasoning backend. The neural visual frontend operates on object-based representation and predicts conditional probability distributions on its attributes. A scene inference engine then aggregates all object attribute distributions to produce a probabilistic scene representation for the backend. The symbolic logical backend abduces, from the representation, hidden rules that govern the time-ordered sequence via inverse dynamics. An execution engine executes the rules to generate an answer representation in a probabilistic planning manner, instead of directly making a categorical choice among the candidates. The final choice is selected based on the divergence between the generated prediction and the given candidates. The entire system is trained end-to-end with a cross-entropy loss and a curricular auxiliary loss without any visual attribute annotations.

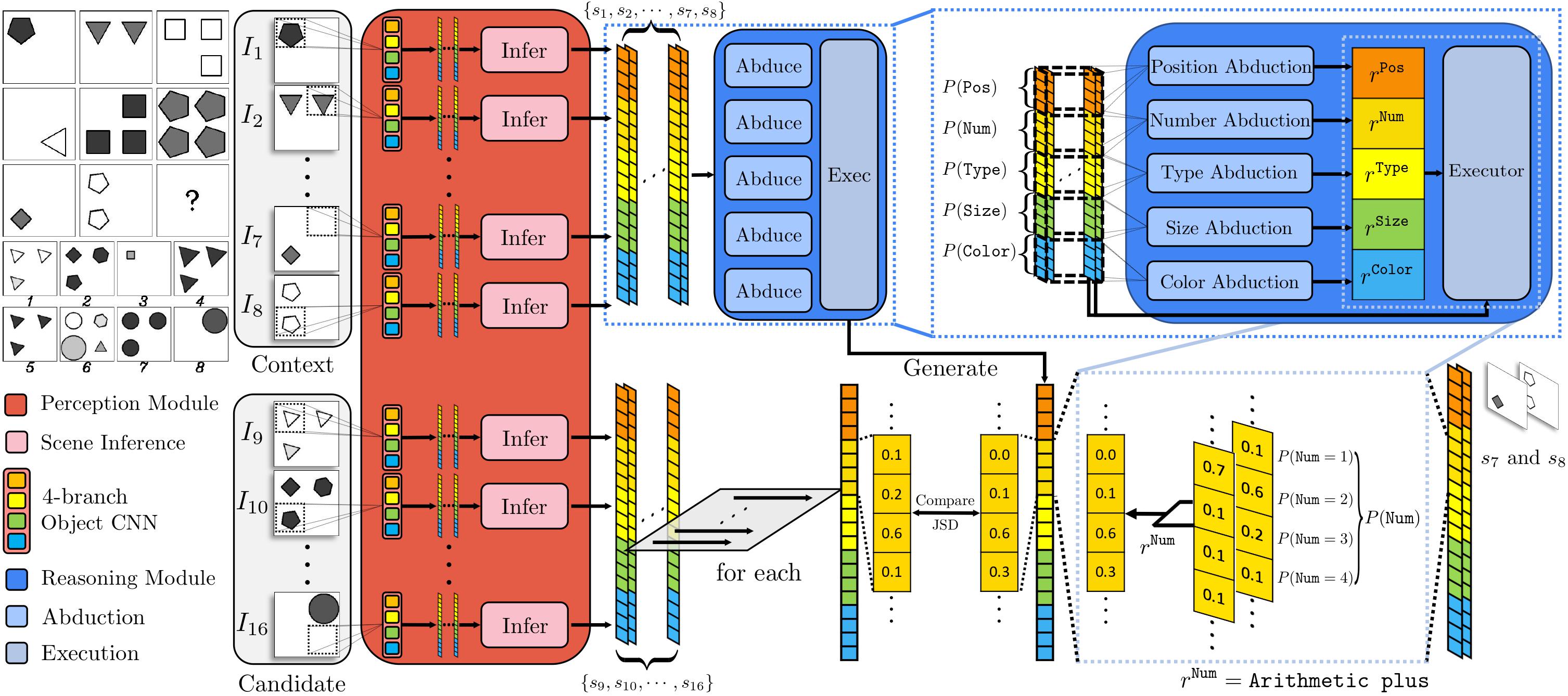

Figure 1. An overview of learning and reasoning of the proposed PrAE learner. Given an RPM instance, the neural perception frontend (in red) extracts probabilistic scene representation for each of the 16 panels (8 contexts + 8 candidates). The Object CNN sub-module takes in each image region returned by a sliding window to produce object attribute distributions (over objectiveness, type, size, and color). The Scene Inference Engine sub-module (in pink) aggregates object attribute distributions from all regions to produce panel attribute distributions (over position, number, type, size, and color). Probabilistic representation for context panels is fed into the symbolic reasoning backend (in blue), which abduces hidden rule distributions for all panel attributes (upper-right figure) and executes chosen rules on corresponding context panels to generate the answer representation (lower-right figure). The answer representation is compared with each candidate representation from the perception frontend; the candidate with minimum divergence from the prediction is chosen as the final answer. The lower-right figure is an example of probabilistic execution on the panel attribute of \(\mathtt{Number}\).

Figure 1. An overview of learning and reasoning of the proposed PrAE learner. Given an RPM instance, the neural perception frontend (in red) extracts probabilistic scene representation for each of the 16 panels (8 contexts + 8 candidates). The Object CNN sub-module takes in each image region returned by a sliding window to produce object attribute distributions (over objectiveness, type, size, and color). The Scene Inference Engine sub-module (in pink) aggregates object attribute distributions from all regions to produce panel attribute distributions (over position, number, type, size, and color). Probabilistic representation for context panels is fed into the symbolic reasoning backend (in blue), which abduces hidden rule distributions for all panel attributes (upper-right figure) and executes chosen rules on corresponding context panels to generate the answer representation (lower-right figure). The answer representation is compared with each candidate representation from the perception frontend; the candidate with minimum divergence from the prediction is chosen as the final answer. The lower-right figure is an example of probabilistic execution on the panel attribute of \(\mathtt{Number}\).

2. The PrAE Learner

2.1 Overview

The proposed neuro-symbolic PrAE learner disentangles previous monolithic visual reasoning into two modules: the neural visual perception frontend and the symbolic logical reasoning backend. The frontend uses a CNN to extract object attribute distributions, later aggregated by a scene inference engine to produce panel attribute distributions. The set of all panel attribute distributions in a panel is referred to as its probabilistic scene representation. The backend retrieves this compact scene representation and performs logical abduction and execution in order to predict the answer representation in a generative manner. A final choice is made based on the divergence between the prediction and each candidate. Using REINFORCE, the entire system is trained without attribute annotations in a curricular manner; see Figure 1 for an overview of PrAE.

2.2 Neural Visual Perception

The neural visual perception frontend operates on each of the 16 panels independently to produce probabilistic scene representation. It has two sub-modules: object CNN and scene inference engine.

2.2.1 Object CNN

Given an image panel \(I\), a sliding window traverses its spatial domain and feeds each image region into a 4-branch CNN. The 4 CNN branches use the same LeNet-like architecture and produce the probability distributions of object attributes, including objectiveness (whether the image region has an object), type, size, and color. Of note, the distributions of type, size, and color are conditioned on objectiveness being true. Attribute distributions of each image region are kept and sent to the scene inference engine to produce panel attribute distributions.

2.2.2 Scene Inference Engine

The scene inference engine takes in the outputs of object CNN and produces panel attribute distributions (over position, number, type, size, and color) by marginalizing over the set of object attribute distributions (over objectiveness, type, size, and color). Take the panel attribute of \(\mathtt{Number}\) as an example: Given \(N\) objectiveness probability distributions produced by the object CNN for \(N\) image regions, the probability of a panel having \(k\) objects can be computed as \begin{equation} P(\mathtt{Number} = k) = \sum_{\substack{B^o \in {0, 1}^N \ |B^o| = k}} \prod_{j=1}^N P(b_j^o = B_j^o), \label{eqn:number_eg} \end{equation} where \(B^o\) is an ordered binary sequence corresponding to objectiveness of the \(N\) regions, \(|\cdot|\) the number of \(1\) in the sequence, and \(P(b_j^o)\) the objectiveness distribution of the \(j\)th region. We assume \(k \geq 1\) in each panel, leave \(P(\mathtt{Number}=0)\) out, and renormalize the probability to have a sum of \(1\). The panel attribute distributions for position, type, size, and color, can be computed similarly.

We refer to the set of all panel attribute distributions in a panel its probabilistic scene representation, denoted as \(s\), with the distribution of panel attribute \(a\) denoted as \(P(s^a)\).

2.3 Symbolic Logical Reasoning

The symbolic logical reasoning backend collects probabilistic scene representation from 8 context panels, abduces the probability distributions over hidden rules on each panel attribute, and executes them on corresponding panels of the context. We assume a set of symbolic logical constraints describing rules is available. For example, the \(\mathtt{Arithmetic}\) \(\mathtt{plus}\) rule on \(\mathtt{Number}\) can be represented as: for each row (column), \(\forall l, m \geq 1\) \begin{equation} (\mathtt{Number}_1 = m) \land (\mathtt{Number}_2 = l) \land (\mathtt{Number}_3 = m + l), \end{equation} where \(\mathtt{Number}_i\) denotes the number of objects in the \(i\)th panel in a row (column). With access to such constraints, we use inverse dynamics to abduce the rules in an instance. They can also be transformed into a forward model and executed on discrete symbols: For instance, \(\mathtt{Arithmetic}\) \(\mathtt{plus}\) deterministically adds \(\mathtt{Number}\) in the first two panels to obtain the \(\mathtt{Number}\) of the last panel.

2.3.1 Probabilistic Abduction

Given the probabilistic scene representation of 8 context panels, the probabilistic abduction engine calculates the probability of rules for each panel attribute via inverse dynamics. Formally, for each rule \(r\) on a panel attribute \(a\), \begin{equation} P(r^a \mid I_1, \ldots, I_8) = P(r^a \mid I_1^a, \ldots, I_8^a), \end{equation} where \(I_i\) denotes the \(i\)th context panel, and \(I_i^a\) the component of context panel \(I_i\) corresponding to \(a\).

To model \(P(r^a \mid I_1^a, \ldots, I_8^a)\), we leverage the compact probabilistic scene representation with respect to attribute \(a\) and logical constraints: \begin{equation} P(r^a \mid I_1^a, \ldots, I_8^a) \propto \sum_{S^a \in \mathtt{valid}(r^a)} \prod_{i = 1}^8 P(s_i^a = S_i^a), \end{equation} where \(\mathtt{valid}(\cdot)\) returns a set of attribute value assignments of the context panels that satisfy the logical constraints of \(r^a\), and \(i\) indexes into context panels. By going over all panel attributes, we have the distribution of hidden rules for each of them.

2.3.2 Probabilistic Execution

For each panel attribute \(a\), the probabilistic execution engine chooses a rule from the abduced rule distribution and executes it on corresponding context panels to predict, in a generative fashion, the panel attribute distribution of an answer. While traditionally, a logical forward model only works on discrete symbols, we follow a generalized notion of probabilistic execution as done in probabilistic planning. The probabilistic execution could be treated as a distribution transformation that redistributes the probability mass based on logical rules. For a binary rule \(r\) on \(a\), \begin{equation} P(s_3^a = S_3^a) \propto \sum_{\substack{(S_2^a, S_1^a) \in \mathtt{pre}(r^a) \ S_3^a = f(S_2^a, S_1^a; r^a)}} P(s_2^a = S_2^a) P(s_1^a = S_1^a), \end{equation} where \(f\) is the forward model transformed from logical constraints and \(\mathtt{pre}(\cdot)\) the rule precondition set. Predicted distributions of panel attributes compose the final probabilistic scene representation \(s_f\).

During training, the execution engine samples a rule from the abduced probability. During testing, the most probable rule is chosen.

2.4 Candidate Selection

With a set of predicted panel attribute distributions, we compare it with that from each candidate answer. We use the Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD) to quantify the divergence between the prediction and the candidate, \begin{equation} d(s_f, s_i) = \sum_a \mathbb{D}_{\text{JSD}}(P(s_f^a) \mid\mid P(s_i^a)), \end{equation} where the summation is over panel attributes and \(i\) indexes into the candidate panels. The candidate with minimum divergence will be chosen as the final answer.

2.5 Learning Objective

During training, we transform the divergence into a probability distribution by \begin{equation} P(\text{Answer} = i) \propto \exp(-d(s_f, s_i)) \end{equation} and minimize the cross-entropy loss.

As the reasoning process involves rule selection, we use REINFORCE to optimize: \begin{equation} \underset{\theta}{\text{min}}\ \mathbb{E}_{P(r)}[\ell(P(\text{Answer}; r), y)], \end{equation} where \(\theta\) denotes the trainable parameters in the object CNN, \(P(r)\) packs the rule distributions over all panel attributes, \(\ell\) is the cross-entropy loss, and \(y\) is the ground-truth answer.

In practice, the PrAE learner experiences difficulty in convergence with cross-entropy loss only, as the object CNN fails to produce meaningful object attribute predictions at the early stage of training. To resolve this issue, we jointly train the PrAE learner to optimize the auxiliary loss. The auxiliary loss regularizes the perception module such that the learner produces the correct rule prediction. The final objective is \begin{equation} \underset{\theta}{\text{min}}\ \mathbb{E}_{P(r)}[\ell(P(\text{Answer}; r), y)] + \sum_a \lambda^a \ell(P(r^a), y^a), \end{equation} where \(\lambda^a\) is the weight coefficient, \(P(r^a)\) the distribution of the abduced rule on \(a\), and \(y^a\) the ground-truth rule. In reinforcement learning terminology, one can treat the cross-entropy loss as the negative reward and the auxiliary loss as behavior cloning.

3. Experimental Results

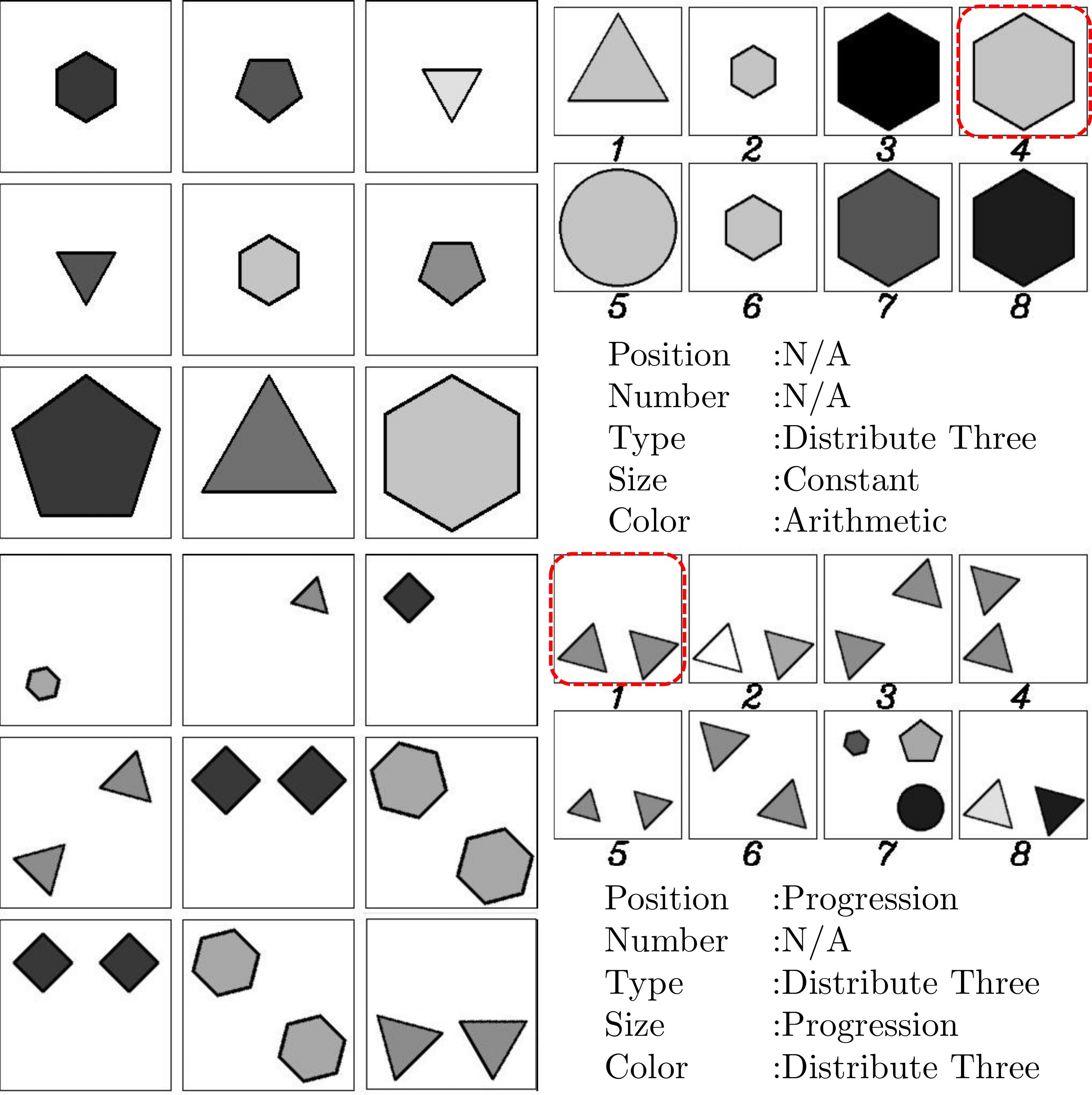

We demonstrate the efficacy of the proposed PrAE learner in RPM. In particular, we show that the PrAE learner achieves the best performance among all baselines in the cross-configuration generalization task of RPM (Table 1). In addition, the modularized perception and reasoning process allows us to probe into how each module performs in the RPM task and analyze the PrAE learner’s strengths and weaknesses (Table 2 and Table 3). Furthermore, we show that probabilistic scene representation learned by the PrAE learner can be used to generate an answer when equipped with a rendering engine (Figure 2).

| Method | Acc | Center | 2x2Grid | 3x3Grid | L-R | U-D | O-IC | O-IG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WReN | 9.86/14.87 | 8.65/14.25 | 29.60/20.50 | 9.75/15.70 | 4.40/13.75 | 5.00/13.50 | 5.70/14.15 | 5.90/12.25 |

| LSTM | 12.81/12.52 | 12.70/12.55 | 13.80/13.50 | 12.90/11.35 | 12.40/14.30 | 12.10/11.35 | 12.45/11.55 | 13.30/13.05 |

| LEN | 12.29/13.60 | 11.85/14.85 | 41.40/18.20 | 12.95/13.35 | 3.95/12.55 | 3.95/12.75 | 5.55/11.15 | 6.35/12.35 |

| CNN | 14.78/12.69 | 13.80/11.30 | 18.25/14.60 | 14.55/11.95 | 13.35/13.00 | 15.40/13.30 | 14.35/11.80 | 13.75/12.85 |

| MXGNet | 20.78/13.07 | 12.95/13.65 | 37.05/13.95 | 24.80/12.50 | 17.45/12.50 | 16.80/12.05 | 18.05/12.95 | 18.35/13.90 |

| ResNet | 24.79/13.19 | 24.30/14.50 | 25.05/14.30 | 25.80/12.95 | 23.80/12.35 | 27.40/13.55 | 25.05/13.40 | 22.15/11.30 |

| ResNet+DRT | 31.56/13.26 | 31.65/13.20 | 39.55/14.30 | 35.55/13.25 | 25.65/12.15 | 32.05/13.10 | 31.40/13.70 | 25.05/13.15 |

| SRAN | 15.56/29.06 | 18.35/37.55 | 38.80/38.30 | 17.40/29.30 | 9.45/29.55 | 11.35/28.65 | 5.50/21.15 | 8.05/18.95 |

| CoPINet | 52.96/22.84 | 49.45/24.50 | 61.55/31.10 | 52.15/25.35 | 68.10/20.60 | 65.40/19.85 | 39.55/19.00 | 34.55/19.45 |

| PrAE Learner | 65.03/77.02 | 76.50/90.45 | 78.60/85.35 | 28.55/45.60 | 90.05/96.25 | 90.85/97.35 | 48.05/63.45 | 42.60/60.70 |

| Human | 84.41 | 95.45 | 81.82 | 79.55 | 86.36 | 81.81 | 86.36 | 81.81 |

Table 1. Model performance (\(\%\)) on RAVEN / I-RAVEN. All models are trained on 2x2Grid only. Acc denotes the mean accuracy. L-R is short for the Left-Right configuration, U-D Up-Down, O-IC Out-InCenter, and O-IG Out-InGrid.

| Object Attribute | Acc | Center | 2x2Grid | 3x3Grid | L-R | U-D | O-IC | O-IG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objectiveness | 93.81/95.41 | 96.13/96.07 | 99.79/99.99 | 99.71/97.98 | 99.56/95.00 | 99.86/94.84 | 71.73/88.05 | 82.07/95.97 |

| Type | 86.29/89.24 | 89.89/89.33 | 99.95/95.93 | 83.49/85.96 | 99.92/92.90 | 99.85/97.84 | 91.55/91.86 | 66.68/70.85 |

| Size | 64.72/66.63 | 68.45/69.11 | 71.26/73.20 | 71.42/62.02 | 73.00/85.08 | 73.41/73.45 | 53.54/62.63 | 44.36/40.95 |

| Color | 75.26/79.45 | 75.15/75.65 | 85.15/87.81 | 62.69/69.94 | 85.27/83.24 | 84.45/81.38 | 84.91/75.32 | 78.48/82.84 |

Table 2. Accuracy (\(\%\)) of the object CNN on each attribute, reported as RAVEN / I-RAVEN. The CNN module is trained with the PrAE learner on 2x2Grid only without any visual attribute annotations. Acc denotes the mean accuracy on each attribute.

| Panel Attribute | Acc | Center | 2x2Grid | 3x3Grid | L-R | U-D | O-IC | O-IG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos/Num | 90.53/91.67 | - | 90.55/90.05 | 92.80/94.10 | - | - | - | 88.25/90.85 |

| Type | 94.17/92.15 | 100.00/95.00 | 99.75/95.30 | 63.95/68.40 | 100.00/99.90 | 100.00/100.00 | 100.00/100.00 | 86.08/77.60 |

| Size | 90.06/88.33 | 98.95/99.00 | 90.45/89.90 | 65.30/70.45 | 98.15/96.78 | 99.45/92.45 | 93.08/96.13 | 77.35/70.78 |

| Color | 87.38/87.25 | 97.60/93.75 | 88.10/85.35 | 37.45/45.65 | 98.90/92.38 | 99.40/98.43 | 92.90/97.23 | 73.75/79.48 |

Table 3. Accuracy (\(\%\)) of the probabilistic abduction engine on each attribute, reported as RAVEN / I-RAVEN. The PrAE learner is trained on 2x2Grid only. Acc denotes the mean accuracy on each attribute.

Figure 2. Two RPM instances with the final 9th panels filled by our generation results. The ground-truth selections are highlighted in red squares, and the ground-truth rules in each instance are listed. There are no rules on position and number in the first instance of the Center configuration, and the rules on position and number are exclusive in the second instance of 2x2Grid.

Figure 2. Two RPM instances with the final 9th panels filled by our generation results. The ground-truth selections are highlighted in red squares, and the ground-truth rules in each instance are listed. There are no rules on position and number in the first instance of the Center configuration, and the rules on position and number are exclusive in the second instance of 2x2Grid.

4. Conclusion

We propose the Probabilistic Abduction and Execution (PrAE) learner for spatial-temporal reasoning in Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM) that decomposes the problem-solving process into neural perception and logical reasoning. While existing methods on RPM are merely discriminative, the proposed PrAE learner is a hybrid of generative models and discriminative models, closing the loop in a human-like, top-down bottom-up bi-directional reasoning process. In the experiments, we show that the PrAE learner achieves the best performance on the cross-configuration generalization task on RAVEN and I-RAVEN. The modularized design of the PrAE learner also permits us to probe into how perception and reasoning work independently during problem-solving. Finally, we show the unique generative property of the PrAE learner by filling in the missing panel with an image produced by the values sampled from the probabilistic scene representation.

However, the proposed PrAE learner also has limits. As shown in our experiments, probabilistic abduction can be a double-edged sword in the sense that when the number of objects increases, uncertainties over multiple objects will accumulate, making the entire process sensitive to perception performance. Also, complete probability marginalization introduces a challenge for computational scalability; it prevents us from training the PrAE learner on more complex configurations such as 3x3Grid. One possible solution might be a discrete abduction process. However, jointly learning such a system is non-trivial. It is also difficult for the learner to perceive and reason based on lower-level primitives, such as lines and corners. While, in theory, a generic detector of lines and corners should be able to resolve this issue, no well-performing systems exist in practice, except those with strict handcrafted detection rules, which would miss the critical probabilistic interpretations in the entire framework. The PrAE learner also requires strong prior knowledge about the underlying logical relations to work, while an ideal method should be able to induce the hidden rules by itself. Though a precise induction mechanism is still unknown for humans, an emerging computational technique of bi-level optimization may be able to house perception and induction together into a general optimization framework.

While we answer questions about generalization and generation in RPM, one crucial question remains to be addressed: How perception learned from other domains can be transferred and used to solve this abstract reasoning task. Unlike humans that arguably apply knowledge learned from elsewhere to solve RPM, current systems still need training on the same task to acquire the capability. While feature transfer is still challenging for computer vision, we anticipate that progress in answering transferability in RPM will help address similar questions and further advance the field.

If you find the paper helpful, please cite us.

@inproceedings{zhang2021abstract,

title={Abstract Spatial-Temporal Reasoning via Probabilistic Abduction and Execution},

author={Zhang, Chi and Jia, Baoxiong and Zhu, Song-Chun and Zhu, Yixin},

booktitle={Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)},

year={2021}

}

References

[1] Fodor, Jerry A., and Zenon W. Pylyshyn. “Connectionism and cognitive architecture: A critical analysis.” Cognition 28.1-2 (1988): 3-71.

[2] Marcus, Gary F. “Rethinking eliminative connectionism.” Cognitive psychology 37.3 (1998): 243-282.

[3] Marcus, Gary F. The algebraic mind: Integrating connectionism and cognitive science. MIT press, 2019.

[4] Dehaene, Stanislas, et al. “Core knowledge of geometry in an Amazonian indigene group.” Science 311.5759 (2006): 381-384.

[5] Izard, Véronique, et al. “Flexible intuitions of Euclidean geometry in an Amazonian indigene group.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108.24 (2011): 9782-9787.

-

Previous

Learning Perceptual Inference by Contrasting -

Next

ACRE: Abstract Causal REasoning Beyond Covariation